Research in motion

07/22/2016Neuroscientist Barbara Händel investigates the connection of rhythmic movement and perception. Her work is funded by the European Research Council with a EUR 1.5 million Starting Grant.

When neuroscientists study which areas of the brain are active during certain processes, they like to put their test subjects into magnetic resonance tomographs. Wedged in the tight tube, they are not allowed to move, have to look straight ahead and must not blink if possible. Other methods that visualize brain activation also require the test subjects to keep as still as possible.

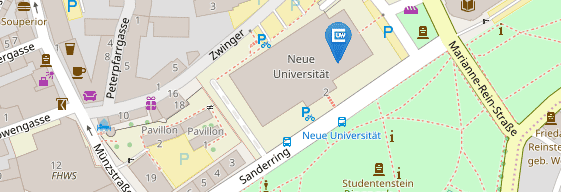

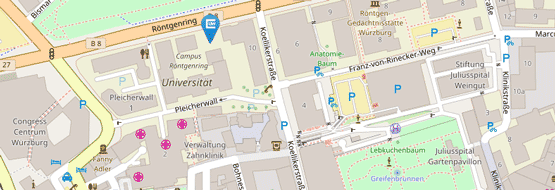

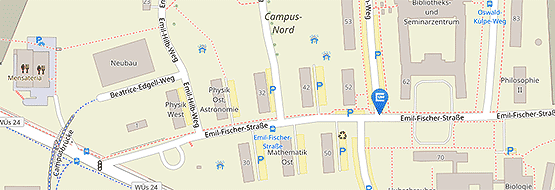

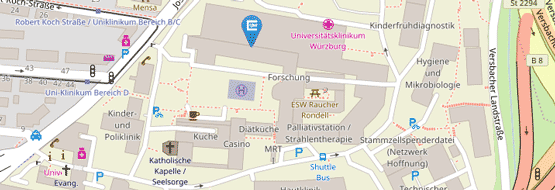

How significant is the data on the processes in our brains thus gathered for natural behaviour? Over the next five years, Dr. Barbara Händel will look into this any many more questions at the Department of Psychology III of the University of Würzburg. For this purpose, she has been awarded one of the coveted EUR 1.5 million "Starting Grants" which the European Research Council (ERC) grants to excellent up-and-coming researchers.

Motionlessness is unnatural

"People are constantly moving. Even when they sit, they are not entirely motionless. And even then at least their eyes are still moving. Looked at in this way, experiments that require participants to stay absolutely still and where eye movement is restricted are very unnatural." Barbara Händel is interested in what this means for the research and its results. Or, in general: How do movements influence human perception?

"By now, we have learned from experiments mainly with animals that rhythmic movements influence various brain activities," the neuroscientist says. In mice, for example, the activation level of the neurons responsible for processing visual stimuli changes depending on the animals' speed of movement – and surprisingly even in complete darkness when the visual input is unaffected by the motion. Simply put, the brain seems to adjust to having to process motion-related stimuli differently than when the animal is at rest.

Technical progress is key

In the coming years, Barbara Händel will study whether this finding also applies to humans. The technical progress allows her to further her project. "In the past, test subjects had to sit still when we measured brain waves using EEG," the scientist explains. Today, the test subjects can wear caps that send their EEG data wireless to the next laptop computer. Also there are portable wireless motion sensors and special glasses that register eye movements. "So it is possible to fit people with wearable equipment and measure what happens in the brain while they move," Händel further.

Her research project is based on the idea that planned, rhythmically recurring motion sequences have an impact on the perception of external stimuli. "Since we are moving most of the time, a certain 'underlying logic' would require our perception processes to attune to this fact," the researcher says. However, this theory has only been backed by initial findings so far. She therefore wants to establish initially whether these mechanisms exist and whether they can be proved in perception and in perception-relevant processes in the brain.

Barbara Händel refers to her work as fundamental research. According to her, the focus is not on concrete applicability – although this is at least conceivable. "How the brain changes its workings in motion is interesting not just for perception research," she says.

Insight into how our movements and perception interact can be valuable for many different areas of research. For example, a lot of degenerative diseases affect both motor activity and cognitive skills and recent studies have shown that training motor activity along with auditory stimulation can have a positive impact on the perceptive performance of patients suffering from Parkinson's disease.

Curriculum of Barbara Händel

Barbara Händel moved from Frankfurt to the University of Würzburg a few weeks ago. In Frankfurt she had worked at Ernst Strüngmann Institute (ESI) for Neuroscience in Cooperation with Max Planck Society. She started her scientific career by studying biology – first in Regensburg and later in Bielefeld, because the university there offered course specialisation in human behaviour.

After graduating (2002), Barbara Händel relocated to the University of Tübingen where she researched functional correlates of perceptual decisions in humans for her dissertation at the Center of Neurology. Subsequently, she joined F.C.Donders Centre for Cognitive Neuroimaging in Nijmegen in the Netherlands.

What prompted her to move from Frankfurt to Würzburg recently? "There is very exciting research going on here in the fields of action and perception and their interrelations," she explains. She believes that her expertise in neuronal processing of sensory stimuli along with her methodical skills will enable her to make a contribution that benefits everyone involved.

Contact

Dr. Barbara Händel, Department of Psychology III

Phone: +49 931 31-84194, Email: barbara.haendel@uni-wuerzburg.de