Warning from the Scientific Community: Beware of AI-based Deception Detection

05/02/2024Artificial intelligence may soon help to identify lies and deception. However, a research team from the Universities of Marburg and Würzburg warns against premature use.

Oh, if only it were as easy as with Pinocchio. Here it was simple to see when he was telling a lie: after all, his nose grew a little longer each time. In reality, it is much more difficult to recognize lies and it is only understandable that scientist have already for a long time been trying to develop valid deception detection methods.

Now, much hope has been placed in artificial intelligence (AI) to achieve this goal, for example in the attempt to identity travelers with criminal intentions at the EU borders of Hungary, Greece and Latvia.

A Valuable Tool for Basic Research

Researchers at the Universities of Marburg and Würzburg are now warning against the premature use of AI to detect lies. In their opinion, the technology is a potentially valuable tool for basic research to gain a better insight into the psychological mechanisms that underlie deception. However, they are more than skeptical about its application in real-life contexts.

Kristina Suchotzki and Matthias Gamer are responsible for the study, which has now been published in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Kristina Suchotzki is a professor at the University of Marburg; her research focuses on lies and how to detect them. Matthias Gamer is a professor at the University of Würzburg. One of his main areas of research is credibility diagnostics.

Three Central Problems for an Applied Use

Suchotzki and Gamer identify three main problems in current research on AI-based deception detection in their publication: a lack of explainability and transparency of the tested algorithms, the risk of biased results and deficits in the theoretical foundation. The reason for this is clear: "Unfortunately, current approaches have focused primarily on technical aspects at the expense of a solid methodological and theoretical foundation," they write.

In their article, they explain that many AI algorithms suffer from a "lack of explainability and transparency". It is often unclear how the algorithm arrives at its result. With some AI applications, at a certain point even the developers can no longer clearly understand how a judgment is reached. This makes it impossible to critically evaluate the decisions and discuss the reasons for incorrect classifications.

Another problem they describe is the occurrence of "biases" in the decision-making process. The original hope was that machines would be able to overcome human biases such as stereotypes or prejudices. In reality, however, this assumption often fails due to an incorrect selection of variables that humans feed into the model, as well as the small size and lack of representativeness of the data used. Not to mention the fact that the data used to create such systems is often already biased.

The third problem is of a fundamental nature: "The use of artificial intelligence in lie detection is based on the assumption that it is possible to identify a valid cue or a combination of cues that are unique for deception," explains Kristina Suchotzki. However, not even decades of research have been able to identify such unique cues. There is also no theory that can convincingly predict their existence.

High Susceptibility to Errors in Mass Screenings

However, Suchotzki and Gamer do not want to advise against working on AI-based deception detection. Ultimately, it is an empirical question as to whether this technology has the potential to deliver sufficiently valid results. However, in their opinion, several conditions must be met before it should be even considered to use in real life.

"We strongly recommend that decision-makers carefully check whether basic quality standards have been met in the development of algorithms," they say. Prerequisites include controlled laboratory experiments, large and diverse data sets without systematic bias and the validation of algorithms and their accuracy on a large and independent data set.

The aim must be to avoid unnecessary false positives - i.e. cases in which the algorithm mistakenly believes it has detected a lie. There is a big difference between the use of AI as a mass screening tool, for example at airports, and the use of AI for specific incidents, such as the interrogation of a suspect in a criminal case. "Mass screening applications often involve very unstructured and uncontrolled assessments. This drastically increases the number of false positive results," explains Matthias Gamer.

Warning to Politicians

Finally, the two researchers advise that AI-based deception detection should only be used in highly structured and controlled situations. Although there are no clear indicators of lies, it may be possible to minimize the number of alternative explanations in such situations. This increases the probability that differences in behavior or in the content of statements can be attributed to an attempt to deceive.

Kristina Suchotzki and Matthias Gamer supplement their recommendations with a warning to politicians: "History teaches us what happens if we do not adhere to strict research standards before methods for detecting deception are introduced in real life." The example of the polygraph shows very clearly how difficult it is to get rid of such methods, even if evidence of low validity and the systematic discrimination against innocent suspects accumulates later.

Publication

Detecting deception with artificial intelligence: promises and perils. Kristina Suchotzki & Matthias Gamer. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2024.04.002

Contact

Prof. Dr. Kristina Suchotzki, University of Marburg, Department of Psychology, T: +49 6421 28-23859, kristina.suchotzki@uni-marburg.de

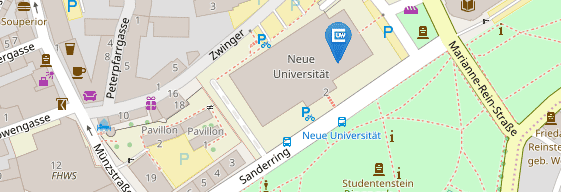

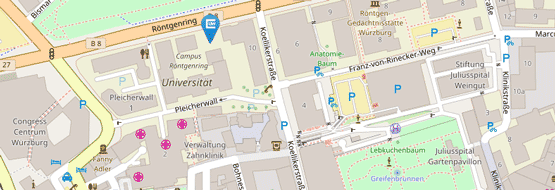

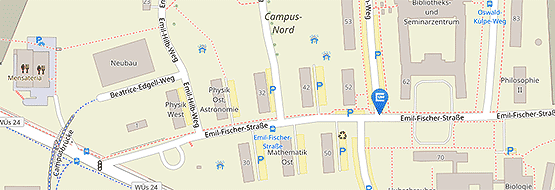

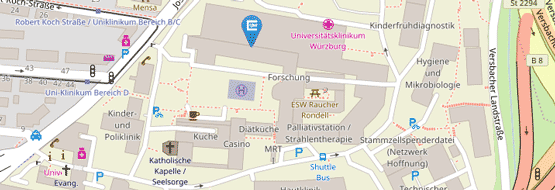

Prof. Dr. Matthias Gamer, University of Würzburg, Department of Psychology I, T: +49 931-31-89722, matthias.gamer@uni-wuerzburg.de