The rectors of the early modern period

After the death of its founder and patron Johann von Egloffstein in 1411, the university could not maintain its teaching activities for much longer. Financial resources were scarce, and the cathedral chapter was only too happy to withhold the necessary professors' salaries, so that both the teaching staff and the student body soon migrated to other cities. Only the clerical education was continued more badly than well. Although there was no continuity in material terms, legally the university continued to exist.

An ambitious prince-bishop wants to revive the university

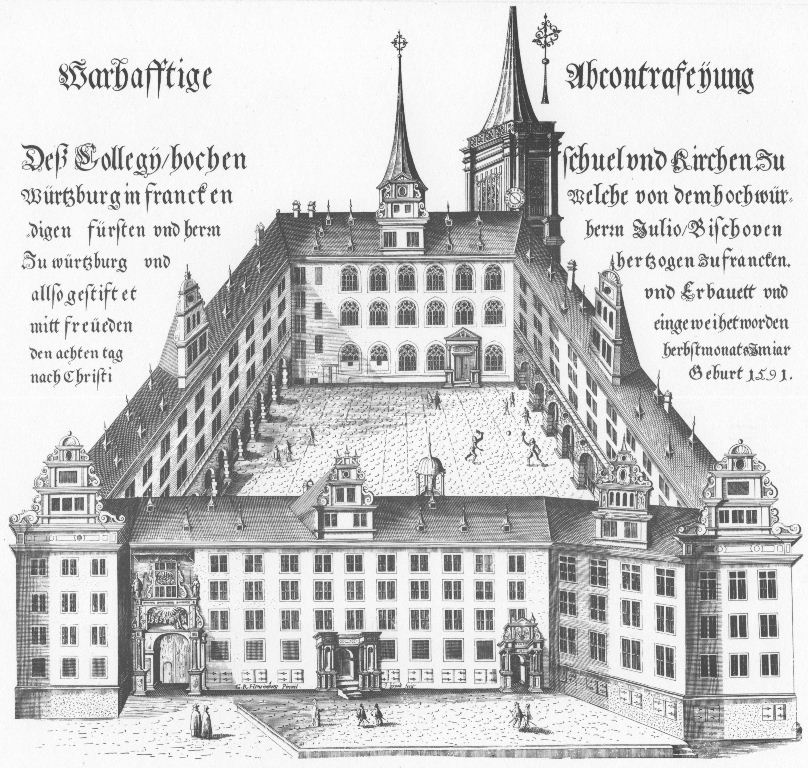

This situation changed with the active Prince-Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn, who decided for various reasons that Würzburg should once again be established as a university location. He was probably encouraged in this decision not least by the economic upswing resulting from the influx of staff and students. Echter applied to the Pope for renewed confirmation of the founding privilege issued in 1402 and also obtained such confirmation from the Emperor. On January 4, 1582, the university constituted itself as a corporation. Afterwards, the graduates present elected Echter as the first rector, who also assumed the role of chancellor at the following graduation ceremony. A first set of university statutes, drawn up in cooperation with the Jesuits, came into force on January 9 of the year of the foundation. On February 11, 1588, new statutes were drawn up and sealed, but only the draft of October 1587 has survived.

The Senate as the most important governing body of the university

The Senate (consilium) was responsible for the management of all the important affairs of the university, thus this body performed the governing functions. It consisted of the rector, the deans and professors of the theological, medical and legal faculties and other approved members of these faculties, followed by the deans of the philosophical and artistic faculties with three elected masters each. The decision-making process followed the Ingolstadt model, according to which, in the event of a tie, the rector had the casting vote.

A celibate man of mature age of conjugal birth, Catholic and "spotless"

At the head of the consilium was the rector, whose term of office was usually one year. He had variously broad powers in the areas of executive, administrative and judicial authority. His duties included presiding over the university court and managing the administration. In addition, there was the representation of the University in public and the use of the University seal. The election always took place on the day of St. Jerome (as the patron saint of students, scholars and scientific associations) on September 30, with confirmation or deselection taking place on the following January 30. At first, only the Faculty of Law had the right to propose candidates for the election of the Rector; from 1597 onwards, this right alternated between the four faculties and, as a fifth group, the members of the University who did not belong to a faculty. Only an unmarried man of mature age and of legitimate birth, who was Catholic and "immaculate", could be elected rector magnificus by the Senate or the consilium. In the case of a rector of nobility, he could be assisted by a prorector. Moreover, immediate re-election was possible and not uncommon. Until the end of the Old Empire, no member of the teaching staff was elected rector; this office was almost universally filled by high clergymen of the city or the prince-bishops themselves. This did not change significantly in the 18th century.

A legal status equal to that of a prince

Unlike today, the university had so-called feudal rights at that time. The stable financial foundation of Echter's reestablishment consisted of a handsome endowment, continuous tax revenues and a wide variety of properties in the Würzburg area, including forests, fields and vineyards as well as entire villages. However, not only the possessions brought with them corresponding sovereign rights over the goods produced there, but also the people living there were subject to the jurisdiction of the university. Here, for example, decisions were made about marriages and arrears of the subjects (so-called Leibherrschaft). The privilege of jurisdiction and administration of justice was also accompanied by certain obligations and rights for the "academic citizenry", i.e. the university members. Thus, these persons enjoyed special protection and were exempt from taxation. The students were subject to university jurisdiction and had to answer to the authorities for offenses such as dueling, drunkenness, immoral behavior or rebellion against the authorities, and they had to expect the appropriate punishments.