Emil Fischer

* 9. October 1852 in Euskirchen † 15. July 1919 in Berlin

1871 Study of Chemistry in Bonn

1872 Transfer to Strasbourg

1874 Promotion

Assistant under Baeyer

1875 Transfer to Munich

1878 Postdoctoral lecture qualification

1879 Professorship in Munich

1882 Professorship in Erlangen

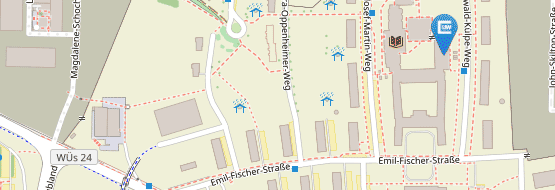

1885 Professorship at the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg

1892 Professorship in Berlin

1902 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In July 2018 the Universitätsarchiv Würzburg wants to use its chance to honour another Nobel Laureate as the scholar of the month. This time the focus lays on Emil Fischer, an excellent Chemist, who felt closely connected to the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, but whose history simultaneously shows the difficulties of his period.

“To stupid to be a businessman...”

After getting his A-Levels in Bonn in 1869, the young Emil Fischer was urging to become a scientist, yet without pleasing his father with this decision. The businessman wanted his son to pursue a commercial apprenticeship, which he first did, before aborting it being frustrated little later. Only then, - Fischer himself conveyed in his Autobiography a quote of his father, that his son was “to stupid to be a businessman, and shall study” - Fischer was allowed to start studying. His decision fell on chemistry, not at last because of his childhood experiences in his father’s dyeing factory. He was a docile student, however could not get along with Kekulés style of lecturing in Bonn. Thereon Fischer wanted to change his subject to physics, which was prevented by his cousin Otto. He then transferred to Strasbourg, where Adolf von Baeyer was recently appointed to, who could not only enthuse Fischer way more, but also made him his assistant.

“The first synthesis of natural Sugar...”

Fischers indelible reputation is founded on his fundamental work on organic chemistry: Thanks to his remarkably sharp and analytical mind, Fischer was able to achieve groundbreaking success in researching the physical structure of natural products, despite the limited possibilities of his period. Especially his works on sugar helped him to gain decent fame, as he was the first to synthesize glucose, but he also did detailed research on peptides and amino acids. For his findings in the glucose chemistry, Fischer was awarded with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Moreover a system for the spatially depiction of carbohydrates – the Fischer projection – was named after him.

“My decision would have been rapidly made...”

The seven years that Fischer spent in Würzburg can retrospectively be described as the happiest of his life: Here, he married his wife, which soon delivered him three sons. The major part of his research on sugar was conducted here. The ministry of culture and education granted him a considerable sum for the new construction of the Institute of Chemistry on the Pleicher Ring, which was partly planed by Fischer, with being finished by his successor Arthur Hantzsch and brought one of the most advanced facilities of the country to Würzburg. After being appealed to come to Berlin in 1892, Fischer had to make a decision: Either to stay in his now beloved Würzburg, or to accept the appealing offer to come to Berlin. According to his own statement, Fischer on his own would have decided to stay in Würzburg, but was persuaded to transfer to Berlin by the plea of his wife, his father and his colleagues in Berlin, as well as through the promise of great financial resources by the ministry of culture and education in Berlin.

About research on weapons and the “deplorable war”

The year of 1914 brought along steep cuts to the scientific works. Emil Fischer did – just like many of his national and international colleagues – adapt his scientific research to the requirements that came with World War I. It is out of question, that Emil Fischer had - among other things - a consulting function in the development of chemical warfare agents for the deployment on the battlefield. Fischer’s doubts about this topic mainly concerned the technical practicality and the concerns that enemy forces could use the same method against German soldiers. But there is serious evidence, that the progression of the war, the slowly apparent becoming defeat and the death of two of his sons made Fischer become increasingly disillusioned and averse to the initial war enthusiasm. In his Autobiography, as well as in his letters, a deep regret about the loss of his Family and Friends, which the war brought along, is recognizable.

Recommended Readings

Baumann, Timo: Giftgas und Salpeter. Chemische Industrie, Naturwissenschaft und Militär von 1906 bis zum ersten Munitionsprogramm 1914/15, Düsseldorf 2008.

Fischer, Emil: Aus meinem Leben, Berlin 1922.

Koschel, Klaus: Die Entwicklung und Differenzierung des Faches Chemie an der Universität Würzburg, in: Baumgart, Peter: Vierhundert Jahre Universität Würzburg. Eine Festschrift, Neustadt a. A. 1982, S. 703-749.